Reverse engineering macOS app 101

Disclaimer

The following tutorial is provided for educational purposes only. Reverse engineering software, hardware, or any other technology may be prohibited by law or violate the terms of service of the respective product. It is crucial to consult legal counsel to ensure compliance with all applicable laws and regulations before engaging in any reverse engineering activities. The information presented in this tutorial is intended to demonstrate the concepts and techniques of reverse engineering. The authors do not condone or encourage the unauthorized use of reverse engineering to infringe upon intellectual property rights, circumvent security measures, or engage in any form of unethical or illegal behavior. It is the responsibility of the reader to use the knowledge gained from this tutorial ethically and legally. The authors, contributors, and publishers of this tutorial are not liable for any misuse, damage, or legal consequences resulting from the application of the information provided herein. By reading this tutorial, you agree to the terms outlined in this disclaimer. If you do not agree with these terms, you should not proceed. Remember, it is essential to respect the intellectual property rights of others and to abide by the laws and regulations governing reverse engineering in your jurisdiction.

Basic knowledge

Before we proceed, let’s cram some fundamental concepts of computer architecture. The programming languages we use, such as Swift, to write programs are typically referred to as High-Level Languages. These languages abstract away the intricate details of how computers operate. On the other hand, we have Low-Level Languages, which are closer to the hardware compared to high-level languages and provide minimal abstraction from machine instructions. This proximity allows programmers to directly manipulate hardware elements like registers and memory.

However, CPUs operate at the binary level, understanding only 0s and 1s. Therefore, we need a compiler to translate our code into binary instructions that the CPU can comprehend. A set of 0s and 1s translates into an instruction that the CPU executes. Different types of CPU architectures exist, leading to various CPU instruction sets tailored to each architecture.

Create a sample app

Please have Xcode installed.

Let’s create a command-line application for experimentation. Open a text editor of your choice and paste the following Swift code snippet:

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

import Foundation

print("Please enter password:")

let password = readLine() ?? ""

if password == UUID().uuidString {

print("NO WAY!")

} else {

print("Bye Bye")

}

Save this file as crackme.swift. Next, open Terminal, navigate to the directory containing crackme.swift, and run swiftc crackme.swift. This will compile the code and generate an executable binary in the same folder. You can execute the application in Terminal and interact with it, but it will be extremely challenging to trigger the NO WAY! message since the password is dynamically generated at runtime.

Examine the app

We can utilize the strings command to extract the strings used in the application. Additionally, combining grep allows us to filter for specific strings of interest using the format strings <BINARY_PATH> | grep "<KEYWORD>".

1

2

3

4

> strings crackme

Please enter password:

Bye Bye

NO WAY!

By using the file command, we can determine the architecture of a binary file.

1

2

> file crackme

crackme: Mach-O 64-bit executable arm64

It’s worth noting that a binary file may contain multiple architectures for different instruction sets.

1

2

3

4

> file /Applications/Xcode.app/Contents/MacOS/Xcode

/Applications/Xcode.app/Contents/MacOS/Xcode: Mach-O universal binary with 2 architectures: [x86_64:Mach-O 64-bit executable x86_64] [arm64:Mach-O 64-bit executable arm64]

/Applications/Xcode.app/Contents/MacOS/Xcode (for architecture x86_64): Mach-O 64-bit executable x86_64

/Applications/Xcode.app/Contents/MacOS/Xcode (for architecture arm64): Mach-O 64-bit executable arm64

To determine which architecture is used when running the program on your machine, you can utilize the arch command to identify the CPU architecture.

1

2

> arch

arm64

Next, we can employ otool to disassemble the binary into assembly code, revealing the low-level programming language instructions.

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

24

25

26

27

28

29

30

31

32

33

34

35

36

37

38

39

40

41

42

> otool -arch arm64 -tvV crackme

crackme:

(__TEXT,__text) section

_main:

0000000100003a6c stp x20, x19, [sp, #-0x20]!

0000000100003a70 stp x29, x30, [sp, #0x10]

0000000100003a74 add x29, sp, #0x10

0000000100003a78 sub sp, sp, #0x100

0000000100003a7c mov x0, #0x0

0000000100003a80 bl 0x100003ef0 ; symbol stub for: _$s10Foundation4UUIDVMa

0000000100003a84 stur x0, [x29, #-0x78]

0000000100003a88 ldur x8, [x0, #-0x8]

0000000100003a8c stur x8, [x29, #-0x70]

0000000100003a90 ldr x8, [x8, #0x40]

0000000100003a94 lsr x8, x8, #0

0000000100003a98 add x8, x8, #0xf

0000000100003a9c and x9, x8, #0xfffffffffffffff0

0000000100003aa0 stur x9, [x29, #-0x68]

0000000100003aa4 adrp x16, 1 ; 0x100004000

0000000100003aa8 ldr x16, [x16, #0x58] ; literal pool symbol address: ___chkstk_darwin

0000000100003aac blr x16

0000000100003ab0 ldur x9, [x29, #-0x68]

0000000100003ab4 mov x8, sp

0000000100003ab8 subs x0, x8, x9

0000000100003abc stur x0, [x29, #-0x60]

0000000100003ac0 mov sp, x0

0000000100003ac4 mov w8, #0x1

0000000100003ac8 mov x0, x8

0000000100003acc adrp x8, 1 ; 0x100004000

0000000100003ad0 ldr x8, [x8, #0x50] ; literal pool symbol address: _$sypN

0000000100003ad4 add x1, x8, #0x8

0000000100003ad8 stur x1, [x29, #-0x48]

0000000100003adc bl 0x100003f20 ; symbol stub for: _$ss27_allocateUninitializedArrayySayxG_BptBwlF

0000000100003ae0 stur x0, [x29, #-0x50]

0000000100003ae4 stur x1, [x29, #-0x58]

0000000100003ae8 adrp x0, 0 ; 0x100003000

0000000100003aec add x0, x0, #0xf50 ; literal pool for: "Please enter password:"

0000000100003af0 mov w8, #0x16

0000000100003af4 mov x1, x8

0000000100003af8 mov w8, #0x1

0000000100003afc and w2, w8, #0x1

...

The -t flag displays the contents of the (__TEXT,__text) section. When used with the -v flag, it disassembles the text, and with the -V flag, it symbolically disassembles the operands. The __TEXT section in a Mach-O file contains the executable code and read-only data of a program, while the __text subsection within __TEXT specifically contains the machine code instructions that the CPU will execute.

Since this is just a simple app, there’s only one function - main - and the part we want to crack is within that function. Having identified the function, we can then connect it to the lldb debugger for further disassembly.

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

24

25

26

27

28

29

30

31

32

33

34

35

36

37

38

39

40

41

42

43

> lldb crackme

(lldb) disassemble -A arm64 -bn main

crackme`main:

crackme[0x100003a6c] <+0>: 0xa9be4ff4 stp x20, x19, [sp, #-0x20]!

crackme[0x100003a70] <+4>: 0xa9017bfd stp x29, x30, [sp, #0x10]

crackme[0x100003a74] <+8>: 0x910043fd add x29, sp, #0x10

crackme[0x100003a78] <+12>: 0xd10403ff sub sp, sp, #0x100

crackme[0x100003a7c] <+16>: 0xd2800000 mov x0, #0x0 ; =0

crackme[0x100003a80] <+20>: 0x9400011c bl 0x100003ef0 ; symbol stub for: type metadata accessor for Foundation.UUID

crackme[0x100003a84] <+24>: 0xf81883a0 stur x0, [x29, #-0x78]

crackme[0x100003a88] <+28>: 0xf85f8008 ldur x8, [x0, #-0x8]

crackme[0x100003a8c] <+32>: 0xf81903a8 stur x8, [x29, #-0x70]

crackme[0x100003a90] <+36>: 0xf9402108 ldr x8, [x8, #0x40]

crackme[0x100003a94] <+40>: 0xd340fd08 lsr x8, x8, #0

crackme[0x100003a98] <+44>: 0x91003d08 add x8, x8, #0xf

crackme[0x100003a9c] <+48>: 0x927ced09 and x9, x8, #0xfffffffffffffff0

crackme[0x100003aa0] <+52>: 0xf81983a9 stur x9, [x29, #-0x68]

crackme[0x100003aa4] <+56>: 0xb0000010 adrp x16, 1

crackme[0x100003aa8] <+60>: 0xf9402e10 ldr x16, [x16, #0x58]

crackme[0x100003aac] <+64>: 0xd63f0200 blr x16

crackme[0x100003ab0] <+68>: 0xf85983a9 ldur x9, [x29, #-0x68]

crackme[0x100003ab4] <+72>: 0x910003e8 mov x8, sp

crackme[0x100003ab8] <+76>: 0xeb090100 subs x0, x8, x9

crackme[0x100003abc] <+80>: 0xf81a03a0 stur x0, [x29, #-0x60]

crackme[0x100003ac0] <+84>: 0x9100001f mov sp, x0

crackme[0x100003ac4] <+88>: 0x52800028 mov w8, #0x1 ; =1

crackme[0x100003ac8] <+92>: 0xaa0803e0 mov x0, x8

crackme[0x100003acc] <+96>: 0xb0000008 adrp x8, 1

crackme[0x100003ad0] <+100>: 0xf9402908 ldr x8, [x8, #0x50]

crackme[0x100003ad4] <+104>: 0x91002101 add x1, x8, #0x8

crackme[0x100003ad8] <+108>: 0xf81b83a1 stur x1, [x29, #-0x48]

crackme[0x100003adc] <+112>: 0x94000111 bl 0x100003f20 ; symbol stub for: Swift._allocateUninitializedArray<τ_0_0>(Builtin.Word) -> (Swift.Array<τ_0_0>, Builtin.RawPointer)

crackme[0x100003ae0] <+116>: 0xf81b03a0 stur x0, [x29, #-0x50]

crackme[0x100003ae4] <+120>: 0xf81a83a1 stur x1, [x29, #-0x58]

crackme[0x100003ae8] <+124>: 0x90000000 adrp x0, 0

crackme[0x100003aec] <+128>: 0x913d4000 add x0, x0, #0xf50 ; "Please enter password:"

crackme[0x100003af0] <+132>: 0x528002c8 mov w8, #0x16 ; =22

crackme[0x100003af4] <+136>: 0xaa0803e1 mov x1, x8

crackme[0x100003af8] <+140>: 0x52800028 mov w8, #0x1 ; =1

crackme[0x100003afc] <+144>: 0x12000102 and w2, w8, #0x1

crackme[0x100003b00] <+148>: 0x940000ff bl 0x100003efc ; symbol stub for: Swift.String.init(_builtinStringLiteral: Builtin.RawPointer, utf8CodeUnitCount: Builtin.Word, isASCII: Builtin.Int1) -> Swift.String

crackme[0x100003b04] <+152>: 0xf85a83a9 ldur x9, [x29, #-0x58]

...

After carefully examining the assembly code, we identify the snippet below is the portion that requires modification - specifically tbz w0, #0x0, 0x100003d24. This assembly code implies that if the value in the w0 register is 0, the program will branch to memory address 0x100003d24. Alternatively, if the condition is not met, the CPU will execute the subsequent instruction - b 0x100003c6c. As we observe the presence of NO WAY! at 0x100003c94, we know we should avoid branching to 0x100003d24.

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

24

25

crackme[0x100003c4c] <+480>: 0x940000af bl 0x100003f08 ; symbol stub for: static Swift.String.== infix(Swift.String, Swift.String) -> Swift.Bool

crackme[0x100003c50] <+484>: 0xaa0003e8 mov x8, x0

crackme[0x100003c54] <+488>: 0xf85783a0 ldur x0, [x29, #-0x88]

crackme[0x100003c58] <+492>: 0xb81843a8 stur w8, [x29, #-0x7c]

crackme[0x100003c5c] <+496>: 0x940000ba bl 0x100003f44 ; symbol stub for: swift_bridgeObjectRelease

crackme[0x100003c60] <+500>: 0xb85843a0 ldur w0, [x29, #-0x7c]

crackme[0x100003c64] <+504>: 0x36000600 tbz w0, #0x0, 0x100003d24 ; <+696>

crackme[0x100003c68] <+508>: 0x14000001 b 0x100003c6c ; <+512>

crackme[0x100003c6c] <+512>: 0x52800028 mov w8, #0x1 ; =1

crackme[0x100003c70] <+516>: 0xaa0803e0 mov x0, x8

crackme[0x100003c74] <+520>: 0xb0000008 adrp x8, 1

crackme[0x100003c78] <+524>: 0xf9402908 ldr x8, [x8, #0x50]

crackme[0x100003c7c] <+528>: 0x91002101 add x1, x8, #0x8

crackme[0x100003c80] <+532>: 0xf81383a1 stur x1, [x29, #-0xc8]

crackme[0x100003c84] <+536>: 0x940000a7 bl 0x100003f20 ; symbol stub for: Swift._allocateUninitializedArray<τ_0_0>(Builtin.Word) -> (Swift.Array<τ_0_0>, Builtin.RawPointer)

crackme[0x100003c88] <+540>: 0xf81303a0 stur x0, [x29, #-0xd0]

crackme[0x100003c8c] <+544>: 0xf81283a1 stur x1, [x29, #-0xd8]

crackme[0x100003c90] <+548>: 0x90000000 adrp x0, 0

crackme[0x100003c94] <+552>: 0x913dc000 add x0, x0, #0xf70 ; "NO WAY!"

crackme[0x100003c98] <+556>: 0x528000e8 mov w8, #0x7 ; =7

crackme[0x100003c9c] <+560>: 0xaa0803e1 mov x1, x8

crackme[0x100003ca0] <+564>: 0x52800028 mov w8, #0x1 ; =1

crackme[0x100003ca4] <+568>: 0x12000102 and w2, w8, #0x1

crackme[0x100003ca8] <+572>: 0x94000095 bl 0x100003efc ; symbol stub for: Swift.String.init(_builtinStringLiteral: Builtin.RawPointer, utf8CodeUnitCount: Builtin.Word, isASCII: Builtin.Int1) -> Swift.String

crackme[0x100003cac] <+576>: 0xf85283a9 ldur x9, [x29, #-0xd8]

Modify the binary

There are multiple strategies to tackle this, like adjusting w0 to a non-zero value, converting the tbz instruction into a no-operation (nop), or directly jumping to the desired location. Your creativity is the only limit. For simplicity, we will opt for the nop operation to transform that line into a no-op.

Given that lldb employs a big-endian system, we must reverse-read the instruction code by bytes, shifting 36000600 to 00060036.

Next, we need to reference the ARM documentation to obtain the instruction code for nop, which is 11010101000000110010000000011111, corresponding to D503201F in hexadecimal. Following the big-endian to little-endian conversion, D503201F becomes 1F2003D5.

Subsequently, using any hex editor, open the binary file and substitute 00060036 with 1F2003D5. Once this replacement is made and the patched binary is executed in the terminal, the program may instantly terminate. This occurs because modifying the code invalidates the original signature used to authenticate the binary integrity.

1

2

> ./crackme

[1] 68294 killed ./crackme

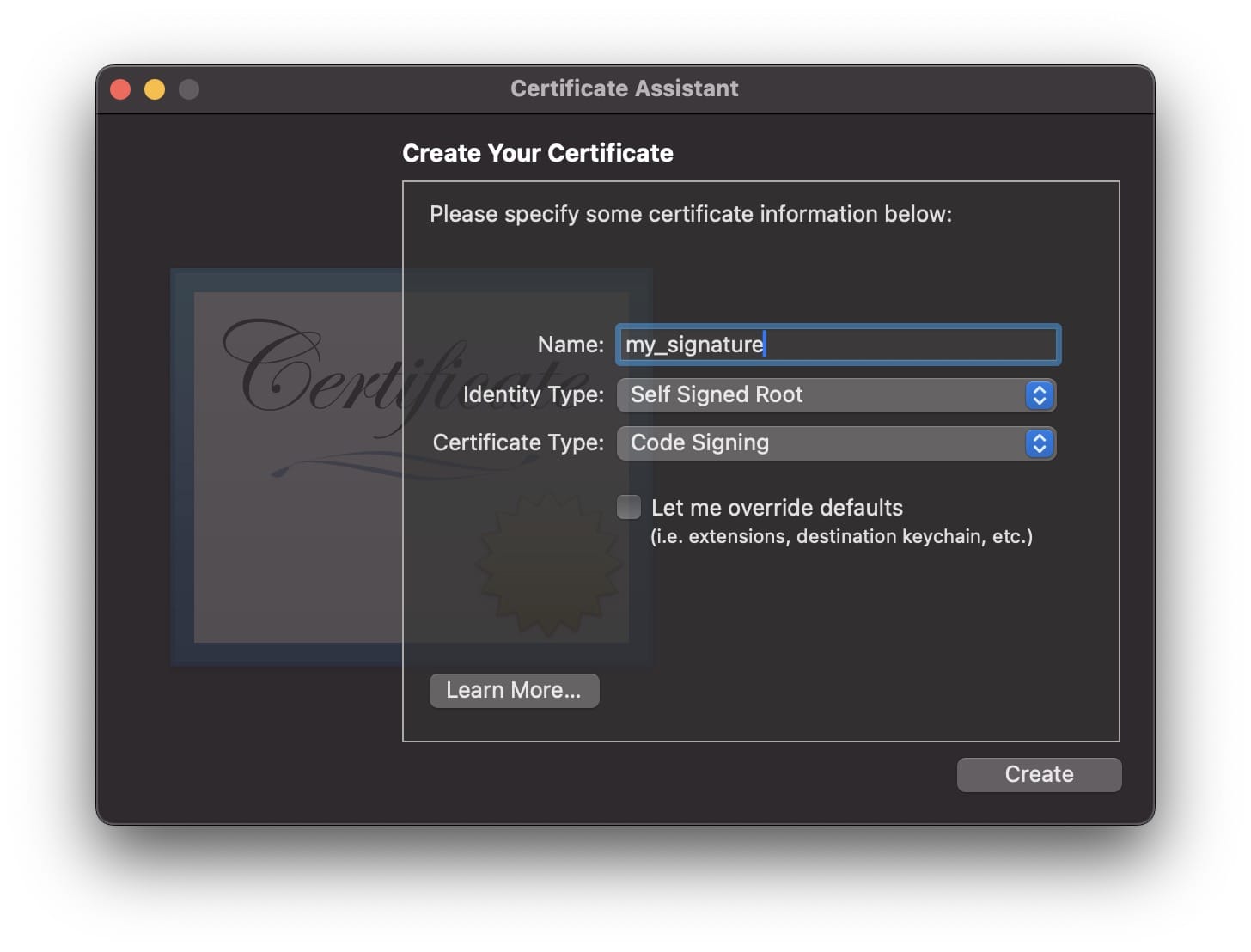

However, this issue can be resolved by generating a custom signature and signing the patched binary. Open Keychain Access.app, navigate to Keychain Access in the top menu bar -> Certificate Assistant -> Create a Certificate.

After creating the signature, in the terminal, execute codesign -fs my_signature crackme. At this point, the process is complete!

Enjoy

Execute the binary in the terminal and input any password. You will observe the message NO WAY! being displayed, signifying the successful bypass of the password verification process.

1

2

3

4

> ./crackme

Please enter password:

123

NO WAY!

Too complicated?

Don’t fret! There are reverse engineering applications available to assist you throughout the process, alleviating concerns about locating the OP code, managing conversions between various endian systems, and more. Personally, I find Hopper Disassembler to be the top choice, while IDA Pro is also widely favored in the field.

Conclusion

The technique demonstrated today is known as static reverse engineering. In contrast, dynamic reverse engineering involves altering the program’s memory at runtime.

It is clear that altering a binary is not excessively difficult, and there exist numerous other methods to exploit a system. When developing a system, it is crucial never to blindly trust input from external applications; always validate inputs to enhance security.